| |

Home

Famous and Fascinating Women in History

Frontiersmen and Women

The World's Greatest Composers

Famous Women Spies

Great Authors of the World

Generals and other Noteworthy People

from the Civil War

The Presidents of the United States

The First Ladies of the United States

Homes and Monuments of and to

Famous People

Historical People and Events by Month for Each Day of the Year!

Famous Figures in Black History

The Calvert Family and the Lords Baltimore

Understanding the American Revolution and its People

Everything Beatles!

Everything Maryland! |

| |

|

|

| |  |  |

|  |

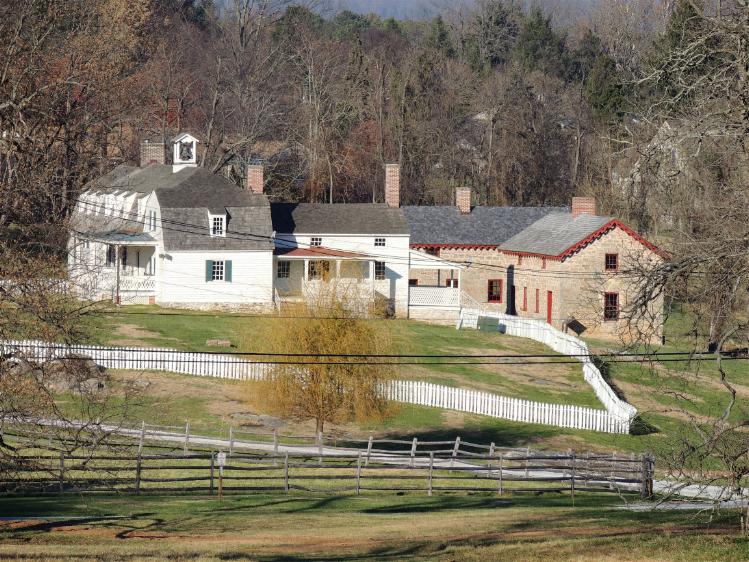

Hampton National Historic Site

Written and Edited by

John T. Marck

Upon visiting

the Hampton National Historic Site and Mansion, you will experience how the

seven generations of the Ridgely family left their legacy. This is seen

through various collections, outbuildings and gardens, and through the Mansion

itself. Each room of the mansion depicts a different era, giving visitors a

total experience of what life was like, living here.

Over

ninety-percent of the objects on display are original. The Mansion, together

with the Lower section that consists of the Overseer’s House, Slave Quarters,

Dairy and Formal gardens offer the complete experience to America’s past. Park

Rangers tell Mansion story of entrepreneurs, indentured servants, slaves and

the changing face of Hampton from 1745 to the present day.

Hampton’s Origin and First Master

The Mansion

estate known as Hampton began and evolved from several tracts of land acquired

by the Ridgely family starting with 1500-acres known as “Northampton” in 1745.

Other land tracts included “Oakhampton,” and “Hampton Court.” The “Hampton”

name is believed to be originated with Colonel Henry Darnell, a relative of

Lord Baltimore for whom the property was originally surveyed in 1695. Darnell

gave Northampton to his daughter, Ann Hill (1680-1749), and she and her two

sons, Henry and Clement, sold the tract to Colonel Charles Ridgely in 1745.

The entire

tract of Northampton, which consisted of houses, outhouses, tobacco houses,

barns, stables, gardens and orchards cost 600 pounds sterling. By 1750,

Colonel Ridgely owned more than 8000 acres in Baltimore and Anne Arundel

Counties. Ridgely, in addition to his being a plantation owner and planter,

was a successful merchant and served in the Maryland Legislature as a

representative for Baltimore County.

The colonel,

having recognized that iron-making was a better economic opportunity than

tobacco farming, established an ironworks in partnership with his sons, John

and Charles. The younger son, Charles, known as captain as he was a mariner

and ship’s captain, married Rebecca Dorsey, the daughter of Caleb Dorsey, and

very prominent and wealthy Anne Arundel County ironmaster. The Northampton

Furnace and Forges, established in 1762, was the tenth such ironworks in

Maryland and they took advantage of the easily mined iron deposits in the

area. The Northampton Company went on to make a substantial fortune for the

Ridgely family both before and during the American Revolutionary War.

Captain

Charles Ridgely had served in the 1750s as a ship captain, and his various

maritime experiences included: Suppressing a mutiny, surviving two hurricanes,

and being captured and imprisoned by the French during the French and Indian

War. In 1763, he retired from his maritime duties, and assumed total control

of the family iron business. However, he did remain an active agent for

British merchants until the Revolutionary War. In addition to his mercantile

business in Baltimore Town, he owned farms that cultivated grain and vegetable

crops, bred cattle, pigs and Thoroughbred horses, and planted a commercial

orchard, as well as operated mills and quarries.

In 1771,

following the death of his brother John, and his father’s death in 1772,

Captain Charles Ridgely owned two-thirds share in the Northampton Ironworks

and therefore maintained control of the entire operation. Running the

ironworks was very labor-intensive. To do so, it relied on a large workforce

that consisted of slaves, indentured servants, convict laborers, and even

British prisoners of war. The war also created a market for the forge’s

products, such as shot, cannons, and camp kettles. The large amounts of income

derived from the various enterprises enabled Ridgely to buy thousands of acres

of land that had been previously confiscated by the British immediately

following the War. In total, Ridgely now had more than 24,000 acres of land.

With his

fortune, Captain Charles Ridgely was now able to afforded his finest

achievement; the building of the Hampton Hall Mansion House. Considered the

“house in the forest,” it began in 1783, as the American revolutionary war was

coming to a close.

In order to

build such a house, workers comprised free craftsmen, indentured servants, and

enslaved African-Americans labored for 7 years, when the house was completed

in 1790. This house represented to Ridgely his “American Dream,” and it stood

as the centerpiece of the Northampton Estate, which comprised 18,000 acres.

Upon completion it was believed to be the largest private home in America at

the time, and served as the summer residence. Captain Ridgely also owned a

house in Baltimore Town, and another on Patapsco Neck in southeastern

Baltimore County.

During the

construction of Hampton Hall, the Ridgely family resided in the Lower House.

Ridgely supervised every aspect of construction as well as the cost. Captain

Ridgely’s wife, Rebecca moved into the Hall in December of 1788, although the

interior was not completed until 1790.

Charles Ridgely Carman, Hampton’s Second Master

Living with

Captain Charles Ridgely and his wife Rebecca in the Mansion in 1788 was

Charles Carnan Ridgely (born Charles Ridgely Carnan) and his wife Priscilla

Dorsey Ridgely. Charles Carnan Ridgely was the son of Captain Ridgely’s sister

Achsah and her husband John Carnan. Charles Carnan Ridgely being Captain

Ridgely’s nephew eventually worked as his uncle’s junior partner and would

become the Mansion’s second Master.

Because

Captain Charles Ridgely and his wife Rebecca had no children, Charles Carnan

Ridgely would become their principal heir. In his uncle’s will, he inherited

12,000 acres of land, that included the Hampton Mansion estate, two-thirds

ownership of Northampton Iron Furnace, other ironworks interests, and other

property, on the condition that he change his surname to Ridgely. By an Act

of the Maryland Legislature, November 5, 1790, Charles Ridgely Carnan, his son

Charles, and al their descendants adopted the surname of Ridgely. In Captain

Ridgely will was also established a “courtesy” entail to protect the core of

the Hampton estate: hall, gardens, and grounds and the Home Farm passed

continuously to the eldest Ridgely son. This entail was followed to the letter

until the estate was transferred to the National Park Service in 1948.

Throughout his

life, Charles Carnan Ridgely served as a representative from Baltimore County

in the Maryland Legislature from 1790 to 1795, as a state senator from 1796 to

1800, and a three-term governor of Maryland from 1815 to 1818. He was known

throughout his life as General Ridgely; Charles Carnan Ridgely’s military

record peaked with his appointment as brigadier general in the state militia

in 1796.

John Carman Ridgely, Hampton’s Third Master

Charles

Ridgely the second master serve d as such from 1790 to July 1829, when he died

from an attack of paralysis. He and his wife Priscilla Dorsey Ridgely had

fourteen children together, of which eleven lived to maturity. Upon the death

of Charles (second master) his will instructed that many of his slaves be

manumitted (freed). This manumission of more than 200 people was one of the

largest in Maryland history. The Mansion house and about 4500 acres of land

was bequeathed to his second son, John Carnan Ridgely, (1790-1867) the new

third Master.

John was the

first child born a Hampton Hall in 1790, but his life was different, not

having any of the ambition of the mansions first two masters. In 1812, he

married his wife, Prudence Gough Carroll (1795-1822). Together they would have

six daughters, but none survived childhood. Prudence died in 1822, and in

1828, John married his second wife, Eliza Eichelberger Ridgely, the only child

of Nicholas Greenbury Ridgely, a prominent Baltimore merchant. Although they

believed they were distant cousins, no descent was ever established. They

would have five children, two of whom survived to adulthood. They were Eliza,

called “Didy,” (1828-1894) and Charles (1830-1872).

When Governor

Charles Ridgely died in 1829 (second master), the Hampton estate and its

various business comprising its “empire,” was reduced through division among

eleven heirs. John Ridgely’s inheritance gave him only the courtesy entail of

45 00 acres. The iron business continued to operate through the 1830s but

advances in processing moved the industry to Pennsylvania to places from

Pittsburgh and Scranton. Consequently by 1850, the Ridgely’s ironworks

stopped its operation. Although many of the slaves were freed by Charles’ will

in 1829, John Ridgely purchased 61 more slaves and the practice continued

until 1864. The Hampton plantation now resembled more of an agricultural one

than its previous industrial site.

Although John

never held public office, he instead devoted his time to the estate and had a

passion for horses and outdoor life. In social areas, he was totally eclipsed

by his wife, Eliza, who was consider “one of the loveliest and most

accomplished women ever raised in the city of Baltimore.” Well educated, she

also spoke fluent French and Italian, and was a friend of the Marquis de

Lafayette to whom she met during his visit to Baltimore in 1824.

By the start

of the Civil War, John was elderly so he allowed his son, Charles, (1830-1872)

to manage the Hampton estate when he had done since about the mid-1850s. John

and Eliza died within a few months of each other in 1867.

In January

1861, a group of “sates rights gentlemen,” established the Baltimore County

Horse Guards, formally organized under Maryland’s militia guards. Charles

Ridgely, now managing the estate, was elected captain and chief officer of the

cavalry. After the Baltimore Riot on April 19, 1861, the Horse Guards were set

to Whetstone Point outside Fort McHenry to guard against any confrontation

between citizens of Baltimore and Union troops. During these days they would

patrol York Road to Cockeysville, following retreating Union troops to the

Pennsylvania border, as well as destroy railroad bridges to the north. Captain

John Ridgely appointed Lieutenant John Merryman of the Hayfields Estate to

carry out those orders.

Lieutenant

Merryman was arrested on May 25, 1861 and taken to Fort McHenry. This arrest

was the subject of Roger Brook Taney’s landmark U.S. Supreme Court opinion

ex parte Merryman, dealing with the writ of habeas corpus.

Charles

Ridgely was never arrested but General John Dix of New York, in command of the

Union troops in Baltimore, and a friend of John Ridgely, informed him that a

warrant had been issued for Charles’s arrest. John assured Dix that his son

was not a conspirator against the United States and that he would remain at

Hampton for the balance of the hostilities. The Baltimore County Horse Guard

was then disbanded.

Charles Ridgely, Hampton’s Fourth Master

As Charles was

managing Hampton for his father John originally, he now took over as Hampton’s

fourth Master. Charles had married Margaretta Sophia Howard, his first

cousin, in 1851. Margaretta was the daughter of James and Sophia Ridgely

Howard. Charles and Margaretta had seven surviving children between 1851 and

1869. Four were sons, John, Charles, Howard, and Otho, and three daughters,

Eliza, Juliana Elizabeth, and Margaretta Sophia.

John Ridgely, Hampton’s Fifth Master

Charles died

of typhoid fever at the early age of 42 on March 29, 1872 in Rome, Italy. His

wife, Margaretta and their children returned to Hampton. Their son, John

Ridgely became the Hampton’s fifth Master. He and his wife, Helen and

mother Margaretta, who managed the estate from 1872 to 1900, tried hard to

preserve its former traditions.

Known as

“Captain” John Ridgely was the technical fifth master, but his mother

Margaretta actually ran the day-to-day operation. Upon Margaretta’s death in

1904, the estate was divided among several heirs. Captain John Ridgely

inherited only 1000 acres including the Home Farm.

John Ridgely, Jr., Hampton’s Sixth and Final Master

In 1905 the

Ridgely’s sold their town house in Bolton Hill and began year-round residence

at Hampton. While the lavish and elegant lifestyle of the past had diminished,

the estate was cared for but little improvement was made. The eldest son of

Captain John and Helen Ridgely would eventually become the Hampton’s sixth and

final master. John Ridgely, Jr. (1882-1959) married Louise Roman Humrichhouse

in 1907 and they built a large house located at 503 Hampton Lane. Here they

raised three children, the oldest named John Ridgely III (1911-1990). When

Louise died in 1934, John Ridgely Jr. moved back into the Hampton Mansion.

In 1935, John

Ridgely III, married Lillian Ketchum (1912-1995) and in 1936, moved to Hampton

Mansion.

Captain John

Ridgely died in 1938, having been the master for 66 years. The property

passed to John Ridgely Jr., who was the estate’s last private owner. In 1939

he married a second time to Jane Rodney.

Then John

Ridgely, III and his wife moved from the mansion to the Lower House, the first

Ridgely’s to live there since the 1780s. They left in 1942 when he served in

the Pacific during World War II. They returned in 1943.

John Ridgely

and his second wife Jane Rodney moved to the Lower House which they then

enlarged by adding a four-room wing and modern conveniences. After John’s

death in 1959, Jane retained life tenancy until her death in 1978.

While they

lived in the Lower House, the Mansion House had officially been designed a

national Historic Site on June 22, 1948. The Mansion was restored on both its

interior and exterior and was opened to the public on May 2, 1950. In 19789

the national park service took over the administration of the Mansion and its

60 acres.

The Structures

on the Estate are: The Lower House; The Slave Quarters; The Stables; The Mule

barn; The Long House Granary; The Dairy; The Corncrib; The Log Cabin; and

several outbuildings near the Mansion. Also located here is: The Family

Cemetery, and The Furnace and Mill.

Also of note

are the Gardens and Grounds; the Orangery, the Greenhouses, and the Garden’s

Cottage, and the Entrance and the North Lawn.

Inside the

Mansion are the Period Rooms, They consist of: The Parlour; The Dining Room;

The Drawing Room; The Music Room; The Great Hall; The Master Bedchamber; The

Northeast Bedchamber; and The Guest Bedchamber.

The Parlour

When you visit

the Parlour, you are treated to the Mansion’s earliest period of occupancy. It

functioned then as a type of sitting or family room would today. It was also

used as a bedchamber for 18 months when Captain Charles Ridgely, “The

Builder,” resided in the Mansion. He died in his bed in this room in June

1790, after suffering a stroke. Today the Parlour is reflective of the tastes

and lifestyle of the Captain’s nephew and heir, Governor Charles Carnan

Ridgely, and his wife, Priscilla Hill Dorsey. It is decorated today as it

would have been at that time for activities as a family tea party. The Federal

era furnishings here are a set of chairs made for the Ridgely’s in the 1780s.

The Dining Room

This room is

furnished to show what the Mansion was like between 1810 and 1829 when

Governor Charles Ridgely died. The settings seen here on the table reflect the

Governor’s taste and wealth. During the Christmas holiday, the table is set

for a formal dinner. In the summer months, it is set for a dessert course.

The colors of the Dining Room, that of Prussian blue and ocher, are based on

scientific analysis, and replicate the second layer of paint about 1810. The

wallpaper, “Monuments of Paris,” is a reproduction of the fashionable French

paper available at shops close to the Governor’s townhouse in Baltimore.

About 1810, the door in the northeast corner was added to provide direct

access to an expanded butler’s pantry and the kitchen beyond. Most of the

furniture was purchased by Governor Ridgely and were made in Baltimore between

1810 and 1825.

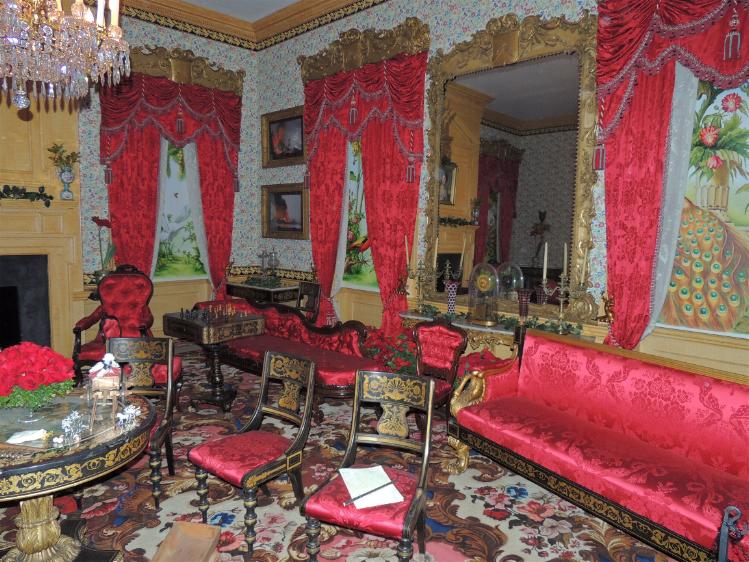

The Drawing Room

This is the

Mansion’s most formal room, and at all times of year contained the best

furniture and decorations. It was used to receive guests, entertain visitors,

and as after dinner receptions. It is furnished today to show what life was

life when John and Eliza Ridgely were master and mistress of Hampton. Of note

is the Baltimore Empire painted sofa with swan arm detail by John Finlay in

1832. Also here are a pair of enormous, custom-made gilded pier mirror and

matching window cornices that bear the family coat of arms supplied to the

Ridgely’s about 1843. Above the fireplace is a portrait painting of Charles

Carnan Ridgely, Jr., by J.W. Jarvis, ca.1812.

The Music Room

Another

fascinating room is the former southwest parlor known as the Music Room since

about the 1840s. At other times this room had other functions to include

serving as the principal library. Seen here are musical instruments including

a harp and piano, used to entertain guests. The harp seen here today was made

for Eliza Ridgely by Sebastian Erard of London in 1817. It was purchased for

Eliza by her father, Nicholas Greenbury Ridgely. The furnishings seen in the

Music Room today are those that reflect the period of a Victorian era about

1870-1890, of Margaretta Howard Ridgely, the widow of Charles Ridgely,

Hampton’s fourth Master. When Margaretta seldom made major purchases, it was

she that acquired the Steinway square grand piano made in New York in 1878.

Research

through historic photographs show the music room filled with furnishings from

previous periods as well as the walls filled with family paintings. These

included portraits of family members from the 19th century to the

late 1870s. The hand-painted window shades are exact copies of the Hampton’s

collection, and feature allegories of Music, Theater and Gardening. Other

items of note, all made in Baltimore, are the large three-part sofa and lady’s

slipper chair made for Eliza Ridgely by the city’s leading cabinetmaker,

Robert Renwick in 1858.

The Great Hall

The

centerpiece of the Mansion is the Great Hall, measuring a very large fifty-one

feet by twenty-one feet. Over the history of the Mansion, this area was used

for many diverse purposes. The first mistress, Rebecca Dorsey Ridgely,

“inaugurated her house-warming by religious services and a watch meeting in

the large-hall.” During Governor Ridgely time, it was used for large parties

and ball. It is noted that one party had 51 people seated for dinner with

plenty of room to spare. Included here today are several pairs of Chinese

porcelain palace jars, the largest placed against the east wall. Despite the

fragile decorations, it is said that Eliza’s children exercised, and threw

snowballs in the Great Hall. In later years it was the site of Didy’s wedding

to John Campbell White. Somber occasions also involved the Great Room that of

the funerals of Eliza and her husband, John Ridgely. The 20th

century brought back its use for balls and other festive activities. During

this time, stained glass was installed in the four principal windows and

lights above the doors gave a chapel-like appearance.

Seen today on

the walls are many portraits, including the young Eliza Ridgely, titled

Lady with a Harp. Also of note here is a Baltimore Federal painted

armchair from a set owned by John Eager Howard, ca.1810.

The Master Bedchamber

On the second

floor in the southwest corner is this room used historically as the principal

bedchamber. It is furnished to represent the period when occupied by Governor

Charles Carnan Ridgely and his wife, Priscilla. Guests would also be received

in the bedchamber, thus the elaborate decoration and furnishings. The painting

over the fireplace was copied from an 18th century view of

Baltimore by George Beck, now at the Maryland Historical Society. As Priscilla

had 14 children, the “lying-in” period after the birth of a child would be

used for friends and neighbors to visit, thus necessitating many chairs, seen

here today. The large mahogany was purchased about 1800, and the bed hangings

are from the 1790s. Also included here is a night table from ca.1800, and the

Beau Brummel, an English Hepplewhite gentlemen’s dressing table,

ca.1800.

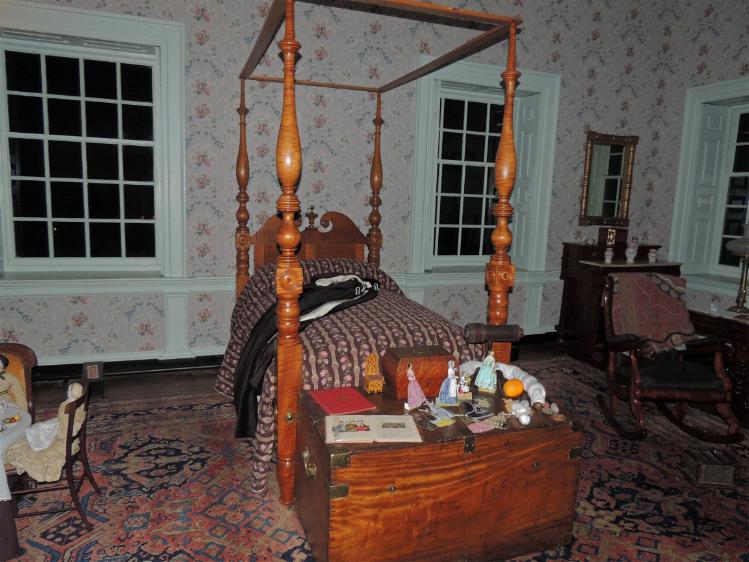

The Northeast Bedchamber

This second

floor room is reflective of a child’s room at the Mansion, showing what daily

life was like for the children of John and Eliza Ridgely. Their two surviving

children, Eliza, called “Didy,” and Charles grew up here and their bedrooms

were on the second floor. The furniture seen here is original from 1820 to

1840. The pair of wardrobes reminds us that there were no built-in closets in

the bedchambers. The maple post bed was made about 1830, probably by John

Needles, Baltimore’s leading Quaker cabinetmaker. On the wall is a Watercolor

painting of a child’s dancing party in Baltimore, ca.1843.

The Guest Bedchamber

This northwest

Bedchamber is furnished to the period from 1890 to 1910, highlighting the era

of Helen Stewart Ridgely, wife of Captain John Ridgely. The focal point is

the pastel portrait of Helen over the fireplace, by Baltimore artist Florence

Mackubin, 1904. Helen was an accomplished woman, as the author of two books,

and her involvement in numerous civic activities and her role in managing the

estate. This room today is viewed as though a female friend was visiting,

showing a suitcase, small trunk, hatbox, and other travel items. In the winter

months, a lady’s riding habit, hat and boots are displayed, suggesting this

visitor may go fox-hunting with the Ridgely’s, a favorite pastime. The top of

the Federal bureau shows ladies dressing accessories, and an English corner

washstand, ca.1810, has English ironstone china washstand set by J. & W.

Ridgway, ca.1830. The room-sized Turkey carpet was purchased by John and

Eliza Ridgely in the late 1850s.

Hampton at Christmas

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

I highly

recommend a visit by all. It is a beautiful Mansion and grounds, with its

wonderful gardens. It should be visited at least twice a year; in the spring

or summer months, and during the Christmas holiday. To me, it’s comparable to

Maryland’s version of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. And, it’s FREE.

Edited by John T.

Marck. Majority of information taken directly from the Hampton National

Historic Site Guidebook, and the National Park Service., Copyright by the

National Park Service at Hampton National Historic Site. The Guidebook was

written by: Gay Vietzke, Superintendent; Vince Vaise, Chief of Interpretation;

Paul Bitzel, Chief of Resource Management; Gregory Weidman, Curator; Debbie

Patterson, Registrar; Kirby Shedlowski, Paul Plamann, and Catherine Holden,

Park Rangers; and Julia Lehnert, Archivist. Production of this guidebook is by

the support of Historic Hampton, Inc.

Also, Copyright

2013 by John T. Marck Informational assistance from the Hampton National

Historic Site and its Park Rangers. All photographs used herein are Copyright

© 2012-2013, by John T. Marck. Information from this article and its

photographs may not be used or reproduced without permission.

A Splendid Time Is Guaranteed For All.

| | |

| |

|