|

You can learn here all

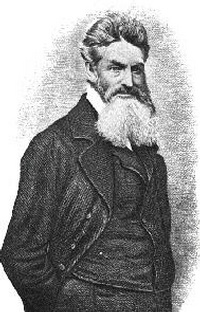

about the abolitionist and fanatical anti slavery fighter, who led a famous

raid on Harpers Ferry, and who became a martyr in parts of the North.

Included here is Brown's last speech before he was led to the gallows

John Brown

By John T. Marck

John Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut on May 9, 1800, the son of a gypsy type family, having moved from place to place throughout New England. However, he spent most of his youth in Ohio, where the schools taught him to take exception to mandatory education. At the same time, his parents taught him to worship the Bible and hate slavery. During the War of 1812, he assisted General William Hull by herding cattle for him. In later years he worked at his family's tannery (tanning is that process of turning animal hide into leather). At the age of twenty, he married Dianthe Lusk, and together they had seven children. Tied of working at his family's business, he and his wife moved to Pennsylvania and operated a tannery of their own. In 1831, Dianthe died, and within a year of her death, Brown married the sixteen-year-old Mary Anne Day. With Mary, they had thirteen children, giving Brown a total of twenty children between his two wives.

Over the next twenty-four years, Brown was not very successful in business, having built and sold several tanneries. Additionally, he was a land speculator, raised sheep, and started a brokerage house for wool growers, all of which did not fair well. Being a bad businessman, he experienced financial difficulties, but rather than improve his situation, his visionary thinking went toward the plight of the weak and persecuted. Always seeking the friendship and company of blacks, he ended up living in a freedman's community in North Elba, New York for two years. Soon he was obsessed in his thinking and became a militant abolitionist, as well as one of the "conductors"

on the Underground Railroad. As well, he was the organizer of the Self-protection League for free blacks and fugitive slaves.

At the age of fifty, Brown now envisioned slave uprisings, and regarded himself as a person commissioned by God to make his visions a reality. In 1855, five of his sons went to Kansas to form a haven for anti slavery settlers, and Brown went along. Following the raids on Lawrence, Kansas, whereby the town was burned and pillaged, Brown's hostility toward slave states accelerated. Seeking revenge, Brown, along with the militia he had formed, went on a mission on the evening of May 23, 1856. With six militia members, as well as four of his sons, they went to the homes of pro-slavery men who lived along the Pottawatomie Creek, dragged them from their homes, and cut them to death with swords. As a result, Brown was known as "Old Brown of Osawatomie," and was feared by those men who were pro-slavery.

By the fall of 1856, Brown had been defeated, for the moment, and returned to Ohio, but still held his vision of a slave rebellion. To accomplish this, Brown traveled back and forth to Kansas several times, now processing a grandiose plan to free the slaves throughout the South. With financial help from abolitionists in New England, Brown started his plan by raiding plantations in Missouri, but accomplished very little by it.

Continuing his plan, in the summer of 1859, he decided to concentrate his mission to western Virginia. So, on the evening of October 16, with an army of twenty-one men that included five blacks, they raided the government armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). It was Brown's plan to steal the arsenal's weapons, then arm thousands of slaves, who he believed would flock to him upon learning of his raid. However, Brown's plan did not work as he had hoped. Instead, groups of the militia as well as the United States Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, converged on Harpers Ferry, trapping Brown and his men in a fire house on October 18. Storming the building, Lee and his men killed ten of Brown's men and captured seven, including Brown.

Later tried and found guilty of treason, John Brown was hanged at Charleston, on December 2, 1859. As a result of Brown's last speech, and his fearless demeanor on the gallows, he became a martyr in sections of the North.

John Brown's Last Speech

"I have, may it please the court, a few words to say.

In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted - the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended, certainly, to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again, on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in a manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case) -- had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends -- either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class -- and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them." I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done -- as I have always freely admitted I have done -- in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right.

Now, it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments -- I submit; so let it be done! Let me say one word further. I feel entirely satisfied with the treatment I have received on my trial.

Considering all the circumstances, it has been more generous than I expected. But I feel no consciousness of guilt. I have stated from the first what was my intention, and what was not. I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of that kind. Let me say, also, a word in regard to the statements made by some of those connected with me. I hear it has been stated by some of them that I have induced them to join me. But the contrary is true. I do not say this to injure them, but as regretting their weakness. There is not one of them but joined me of his own accord, and the greater part of them at their own expense. A number of them I never saw, and never had a word of conversation with, till the day they came to me; and that was for the purpose I have stated. Now I have done."

Copyright ©

1993-2022 by John T. Marck. All Rights Reserved. This article and their accompanying pictures, photographs, and line art, may not be resold, reprinted, or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the author.

|