Here

you can learn all about the first officer to die in the Civil War, who was a

promise to the North, a great symbol of patriotism, and America's foremost

parade-ground soldier.

Colonel

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth

By

John T. Marck

The first officer

to die in the Civil War was Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, a twenty-four-year-old

personal friend of President Lincoln, who appeared to be the Union's most

promising officer. To the North, he was a symbol of patriotism, and America's

foremost parade-ground soldier. He commanded the U.S. Zouave Cadets,

transforming them from a halfhearted group of Chicagoans into a

national-champion drill team. So good was Ellsworth that he developed his own

variations of the Zouave drill, adding hundreds of acrobatic maneuvers with

musket and bayonet.

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth

was born in Malta, New York on April 11, 1837. As a young boy he had always

desired to attend West Point, however, when he became of age, he did not have

the opportunity to study for the entrance exam. Consequently, as a young man,

her left home for New York City, then moved to Chicago where he worked as a law

clerk and a solicitor of patents.

His interest in the

military continued, so he joined a National Guard volunteer company in Chicago

that was about to disband. Bringing them back together, he also recruited new

members through his introduction of the Zouave dress and drill, that was

fashioned after French colonial troops in Algeria. His company's cadets, now

known as the United States Zouave Cadets of Chicago soon became a highly trained

and competent unit. Their unusual dress consisting of baggy pants, short

jackets, fezzes and gaiters, combined with their complicated drills gained

attention for them in the Midwest.

Within a short

time, Ellsworth was appointed a major of the Illinois National Guard, and soon

his unit became the governor's guard. In 1860, before the Civil War began,

Ellsworth and his unit toured all the major cities in the North section of the

United States, including Washington, D.C.

In August of 1860,

Ellsworth left his command temporarily to travel to Springfield, Illinois where

he worked and studied law in the offices of Abraham Lincoln. Becoming a close

friend of Lincoln's, he stayed with him and assisted him in his campaign for

president as well as traveled with him to Washington in the early months of

1861.

Ellsworth had

spoken to Lincoln concerning a position in the War Department, however, this was

put on hold due to the outbreak of the Civil War. As a result, Ellsworth

traveled to New York City where he raised a volunteer regiment. In order to find

the necessary men, he recruited them from the city's fire departments, then

uniformed them in Zouave dress, further training them in the arts of drill. This

regiment, commanded by the now Colonel Ellsworth, was soon designated as the 11th

New York Fire Zouaves.

On May 24, 1861,

the day after Virginia officially seceded, Union troops were ordered to cross

the Potomac River and seize and control important areas on the Virginia side. As

the port of Alexandria was a choice assignment, Ellsworth convinced the powers

that be to give this mission to him and his Fire Zouaves. Ellsworth even dressed

for the occasion, wearing a new gleaning uniform, affixed with a medal that was

inscribed in Latin, "Not for ourselves alone but for country."

Leaving Washington

at daybreak, Ellsworth and his troops traveled by steamer to an Alexandria

wharf. They were met by no resistance, as Alexandria's only Confederate troops,

a small Virginia militia, were hurriedly leaving town. Once there, Ellsworth

ordered one company of his soldiers to take and hold the railroad station, while

he and a small detachment went off to capture the telegraph office.

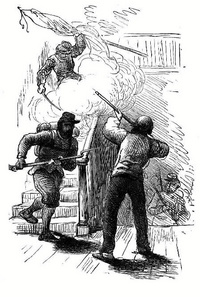

While heading

toward this office, Ellsworth and his men came upon an inn, known as the

Marshall House, on King Street. Glancing up, Ellsworth saw that the inn was

flying a large Confederate flag, and ordered that it be immediately taken down.

After stationing a few of his men on the first floor of the inn, Ellsworth and

four of his men went upstairs and leaning out a window, cut down the flag.

Ellsworth then started back down the stairs. In front of Ellsworth was Corporal

Francis E. Brownell, and behind him was Edward H. House, a reporter for the New

York Tribune. At the landing on the third floor, the innkeeper, James W.

Jackson, was waiting with a double-barrel shotgun. As Jackson raised his weapon

to fire, Corporal Brownell batted the barrel of Jackson's shotgun aside with the

barrel of his musket, to avert the shot. Simultaneously, Jackson fired, hitting

Ellsworth. Jackson then fired a second shot, barely missing Brownell. At the

same time as Jackson's second shot, Brownell fired, striking Jackson. As Jackson

lay dead, Brownell bayoneted his body, sending it falling down the stairs. They

then turned their attention to Ellsworth, who lay dead on top of the bloody

Confederate flag, his uniform medal embedded into his chest from the force of

the shotgun blast.

The death of

Colonel Ellsworth plummeted the North into a state of mourning. Flags flew at

half mast and bells tolled. Upon seeing his friend's body, President Lincoln was

grief-stricken. On May 25, 1861, upon Lincoln's orders, an honor guard brought

Ellsworth's body to the White House, where he lay in state, followed by a

funeral ceremony. Colonel Ellsworth's casket was then moved to City Hall in New

York, where thousands paid their respects. Following this, a train bearing

Ellsworth's remains traveled to his hometown of Mechanicsville, New York, where

he was buried in a grave overlooking the Hudson River.

Following his

death, Colonel Ellsworth became cult-like in the eyes of the Union. Poems,

songs, sermons and memorial envelopes lamented his loss, and parents named their

babies after him, and streets and towns used his name.

Copyright ©1993-2022 by John T. Marck. All Rights Reserved. This article and their

accompanying pictures, photographs, and line art, may not be resold,

reprinted, or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written

permission from the author.

|