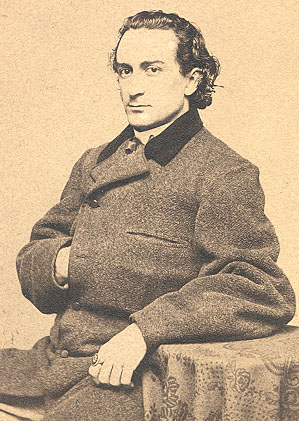

John Wilkes Booth

His Life and Death

by John

T. Marck

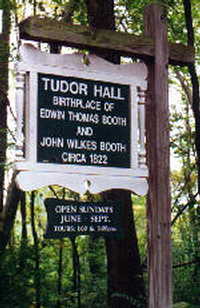

John Wilkes Booth was born on

May 10, 1838 on a small farm known as Tudor Hall, located a few miles outside

of Bel Air, Harford County, Maryland. His parents, Junius Booth and Mary Ann

Holmes were British, and moved to the United States in 1821. John Wilkes was

the ninth born of their ten children. The Booth family stayed on their farm at

Tudor Hall in the warmer months, and also owned and used slaves. During the

winter, they would move to their other home located on North Exeter Street in

Baltimore City. His father, Junius was a very well-known actor.

John Wilkes received his

schooling in Maryland, first at a boarding school in Cockeysville (Baltimore

County) operated by Quakers, after which he attended St. Timothy's Hall, an

Episcopal military academy in Catonsville, also in Baltimore County. As a

young man in the 1850s, Booth joined the Know-Nothing Party. This party was

formed by Americans for the purpose of preserving the country for native-born

white citizens. In 1852, his father died and John left school and spent the

next few years working on their farm near Bel Air.

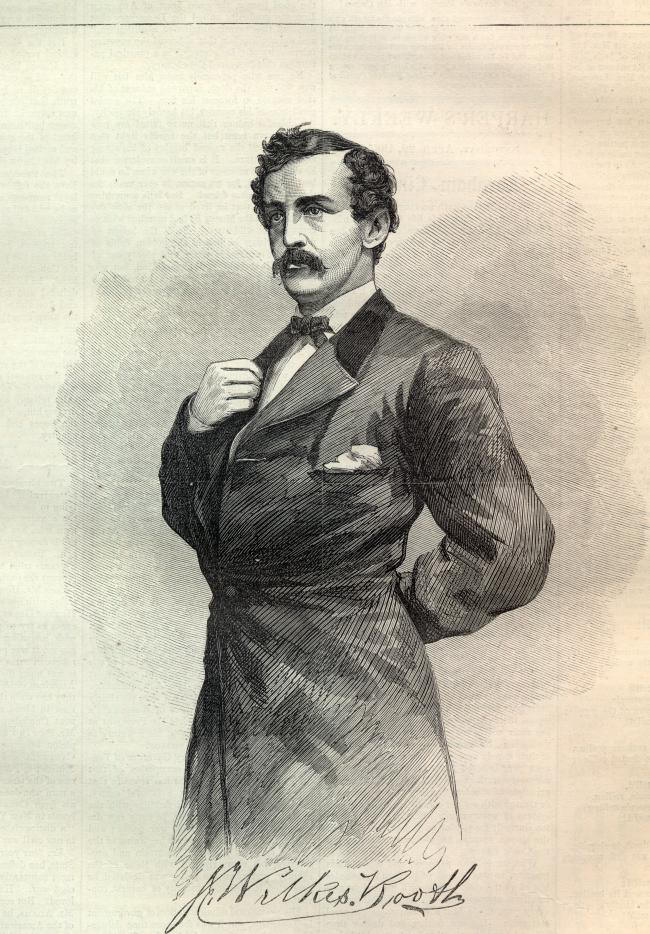

However, farming was not in

John's life plan. According to his sister, Asia Booth Clarke, he had always

wanted to be famous. So, John followed in his father's footsteps toward a

career in acting. In 1855, at the age of seventeen, Booth made his acting

debut in the production of Shakespeare's Richard III, in the role of

the Earl of Richmond. Following this, it would be two years before he again

appeared on stage. He did play minor roles in Philadelphia, but was not well

received, as he would frequently forget his cues and lines. But, desiring to

be a good actor, he did not give up, and finally landed roles in 1858 as part

of the Richmond Theatre. Living in Richmond, he became fascinated with the

people and the Southern way of life. In 1859, Booth witnessed the execution of

John Brown, working as one of the guards stationed there to prevent any

attempts to rescue Brown.

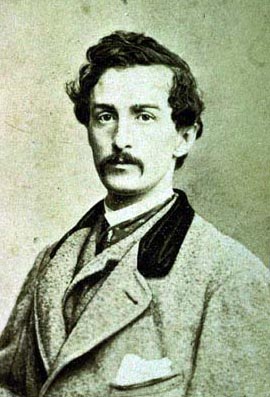

In 1860, his acting career

started to take off. He landed the role as Duke Pescara in The Apostate,

at the Gayety Theatre in Albany, New York. It was here that President Lincoln

passed through Albany en route to Washington, D.C. Booth's acting continued in

such productions as Romeo and Juliet, The Marble Heart, The Merchant of

Venice, Julius Caesar, Othello, The Taming of the Shrew, Hamlet, Macbeth,

and others. His appearances took him to New York, Boston, Baltimore,

Washington, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Leavenworth, Nashville,

New Orleans and Richmond, prior to the Civil War. From November 2 through

November 15, 1863, Booth appeared in The Marble Heart in the role of

Raphael at Ford's theatre in Washington, D.C. It was during his November 9

performance that President Lincoln attended and saw Booth in this role. The

box where Lincoln sat was the same exact spot in which he would be later

assassinated. Following The Marble Heart at Ford's, Booth made only

one more appearance there, when on March 18, 1865, he appeared as Duke Pescara

in The Apostate. Although Booth was considered a good actor, he never

excelled to the level of talent possessed by his father, nor his brother

Edwin, who all worked together in one production of Julius Caesar. In

the play, Booth appeared as Marc Antony, while Edwin played Brutus, and their

father Julius, played Cassius. In the summer of 1864, Booth appeared in a

production at Meadville, Pennsylvania, and stayed in a room at the McHenry

House. Upon checking out, a cleaning woman attending the room found an

inscription on one of the windowpanes that read, "Abe Lincoln departed his

life August 13, 1864, by the effects of poison." Unfortunately, no one

gave it much attention, nor focused on Booth as the writer.

Late in the summer of 1864,

Booth began his plans to kidnap Abraham Lincoln. His idea was to abduct

Lincoln, then take him to Richmond where he would be held for ransom in

exchange for Confederate prisoners held in Union camps. Booth believed this

was one way to increase the deteriorating ranks of Rebel soldiers. To assist

him in his plan, he began recruiting helpers. He was able to recruit Michael

O'Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, Lewis Paine, John Surratt, David Herold and George

Atzerodt. A meeting was set whereby all the members met at Gautier's

Restaurant, a short distance from Ford's Theatre in Washington, and discussed

their abduction plan. A few days after this meeting, Booth became aware that

Lincoln would be attending a play at the Campbell Hospital near Washington,

D.C., on March 17, 1865. To Booth this seemed to be his best opportunity to

abduct Lincoln. That day in March came and Booth's plan was in place. Lincoln

decided at the last minute not to attend the play, but rather to speak to the

140th Indiana Regiment and present a captured Confederate flag to

the Governor of Indiana. As this plan failed, some of Booth's conspirators

became disenchanted and abandoned the group. NOTE: It should be said that many

books say that the abduction attempt actually took place, whereby Booth and

his gang saw Lincoln's carriage and started their plan, but once they realized

Lincoln was not in the carriage, they stopped. This incident never occurred.

In Booth's personal life was

a lady named Lucy Lambert Hale, the daughter of John Parker Hale, an

abolitionist senator from New Hampshire. In early 1865, the Hale family moved

into the National Hotel, in Washington, where Booth was also staying. In the

first days of March 1865, Booth became secretly engaged to Lucy. On March 4,

on the occasion of Lincoln's second inauguration, Booth invited Lucy as a

guest. In his quest for Lincoln, Booth once confided to an actor friend by the

name of Samuel Knapp Chester, that, "What an excellent chance I had to

kill the President, if I had wished, on inauguration day!" Booth and his

conspirators had other plans to kidnap Lincoln, specifically at a theatre, but

these plans fell through. Then on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee

surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant, effectively ending

the Civil War. Two days later, President Lincoln gave a speech at the White

House where he discussed possible new rights for blacks. In the audience were

Booth, Herold and Paine. The speech enraged Booth, and he vowed to silence

Lincoln.

April 14, 1865

The following outlines the

activities John Wilkes Booth, the day of the assassination.

At about 9:00 a.m., Booth met

with his fiancée, Lucy, at the National Hotel. The National Hotel was

originally located at the northeast corner of Sixth Street and Pennsylvania

Avenue. It was demolished in the 1930s. They parted, then he went to Booker

and Stewart's barbershop on E Street. Here barber Charles Wood gave him a

haircut. Upon leaving the barbershop he stopped by the Surratt boardinghouse

and met with Mary Surratt. He then returned to his room, number 228 at the

National Hotel. Booth seemed to be normal in his activities and behavior

according to witnesses who saw him at the hotel. After a short while, Michael

O'Laughlen stopped by his room and visited with Booth.

Two hours later, at 11:00

a.m., Booth went to Ford's Theatre to pick up his mail. While there he spoke

with Henry Clay Ford, who told him that Lincoln was expected to attend that

evenings performance of Our American Cousin. Booth, knowing just

about every line of the play, knew when the greatest laughter would occur. He

figured it would happen at 10:15 p.m., when an actor in the play, Harry Hawk,

would be alone on stage. Booth decided that this was the time to assassinate

President Lincoln.

At about noon, Booth went to

the C Street stable operated by James W. Pumphrey. He asked Pumphrey if he had

a fast horse, and he did, so Booth rented it, saying he would pick it up at

4:00 p.m. Booth then returned to his room at the National

Hotel.

At 2:00 p.m., Booth left the

National Hotel and walked to the Herndon House where Lewis Paine was staying.

Booth advised Paine of his plan, but Booth also had further plans in mind,

whereby he instructed Paine to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward.

He then told Paine that it was time to check out of the Herndon House, which

he did. At about 2:30, Booth stopped by the Surratt boardinghouse and gave

Mary Surratt a package containing field glasses and asked her to take them

with her to her tavern in Surrattsville.

Booth then went to visit

another conspirator named George Atzerodt at the Kirkwood House at about 3:00

p.m. Here Booth intended to discuss his plan for Atzerodt to assassinate

Vice-President Andrew Johnson, who also lived at the Kirkwood House. But,

Atzerodt was not in. Booth then left a note for Vice-President Johnson with

either his personal secretary or the desk clerk, Robert Jones. No one knows

for sure why he left this note, but in any case, Johnson was not in, but

rather was at the White House.

At 4:00 p.m. Booth returned

to the stable and picked up the horse he had rented earlier. He road this

horse to the Grover Theatre where he stopped, and went upstairs to the Deery

Tavern for a drink. While there, he wrote a letter explaining that his plans

for kidnapping the President had changed to murder. He then signed the letter

not only with his name, but also from Paine, Herold and Atzerodt. The letter

was addressed to the editor of the National Intelligencer, a

Washington newspaper. About an hour later, as he walked his horse down

Fourteenth Street, he met a fellow actor named John Mathews, who was appearing

in the play Our American Cousin. He gave him the letter and asked him

to deliver it to the National Intelligencer the next day. He then

mounted his horse and rode away, passing Ulysses S. Grant who was riding in a

carriage. Booth observed Atzerodt walking down the street, and stopped. Booth

told him to murder Andrew Johnson as close to 10:15 p.m. as was possible.

Atzerodt was hesitant to carry out the plan.

At 6:00 p.m., Booth rode his

horse to Ford's Theatre where he invited a few of the employees out for a

drink at Taltavul's Tavern. About thirty minutes later he returned to the

theatre and mapped out his route for the assassination. He practiced and

practiced again everything he would do, except jumping from the stage. Using a

tool known as a gimlet, he drilled a small hole in the door that lead to the

box where Lincoln would be sitting. He then returned to the National Hotel for

dinner and rest.

Awaking a little before 7:00

p.m., Booth readied himself to carry out his plan. He dressed in black

clothes, and calf-length boots with new spurs, and a black hat. He carried

with him his diary, a compass, a small .44 Philadelphia Derringer and a long

Bowie knife. He stuck the knife inside his left side pant leg and loaded the

single shot derringer with a .44 caliber lead ball. At 7:45 he left the

National Hotel.

Nearing 8:00 p.m., he had one

final meeting with his coconspirators, at an unknown location. The final plan

was for Paine to assassinate Seward. Herold was to go with Paine to Seward's

home and assist him in escaping Washington. Atzerodt would shoot and kill

Vice-President Johnson, and Booth was to kill Lincoln. It was Booth's plan

that all the attacks would occur simultaneously at 10:15 p.m. Afterwards they

would all meet at the Navy Yard Bridge. From this location, they would all

travel to Surrattsville where they would pick up weapons and field glasses

from the tavern leased by John Lloyd.

At about 9:30 p.m., Booth

arrived at Ford's Theatre. Outside the theatre he called upon a man named Ned

Spangler to hold his horse in the alley behind the theatre. Spangler was still

busy with stage settings, so he asked another employee named Joseph C.

Burroughs to watch and hold the horse. Booth then went next door to a tavern

and ordered a bottle of whiskey and some water. A customer at the tavern who

knew Booth said to him, "You'll never be the actor your father was."

To this Booth replied, "When I leave the stage, I will be the most famous

man in America."

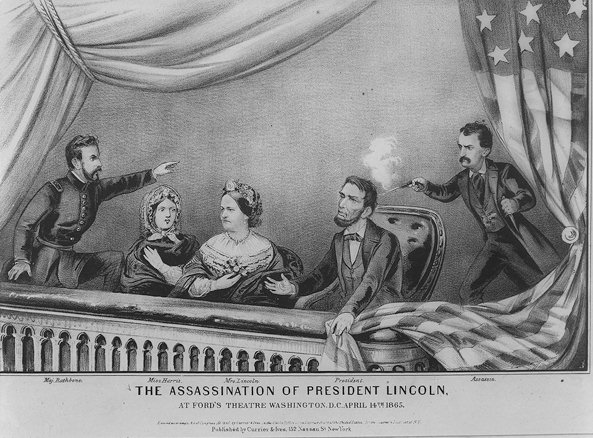

At 10:07 p.m., John Wilkes

Booth entered the lobby of Ford's Theatre. He went upstairs to the dress

circle, and saw in the distance the door that would lead him to Lincoln's

State Box. Seated outside Lincoln's State Box was Charles Forbes, the

President's footman. To get to Lincoln's box Booth had to get

past Forbes. Eventually, he handed Forbes a card that enabled him to pass.

Booth then entered an area that was dark, directly behind the door that lead

to the State Box. He then placed the wooden leg of a music stand that he had

put there earlier in front of the door, to block anyone from entering the

room. Removing the derringer from his pocket, he then opened the door directly

behind where Lincoln was seated. Booth walked a few steps toward the

President, and placed his derringer behind Lincoln's head near his left ear

and pulled the trigger.

As Booth predicted, his shot

rang out during audience laughter, and most did not hear it. Sitting in the

box with Lincoln was Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara H. Harris.

(Although married in 1867, there future was tainted by Rathbone's inability to

forgive himself for not having protected President Lincoln. In time, his

torment drove him mad, and in 1894 he murdered Clara, resulting in him

spending his remaining years in an asylum). As Rathbone tried to subdue the

assassin, Booth pulled his knife and stabbed Rathbone in his left arm. Booth

then climbed over the banister of Lincoln's State Box and jumped eleven feet

to the stage floor. In doing so, the spur on his right foot caught one of the

decorative flags draped from the guardrail, causing him to land off balance,

breaking the fibula bone in his left leg just above his ankle. He pointed his

knife toward the audience, and fled out the back of the theatre, to his

waiting horse, and escaped into the night.

There are two stories as to

what Booth may have shouted just after shooting the President. Some audience

members believe he said "Sic semper Tyrannis," (Thus Always to

Tyrants), while others heard nothing. Major Rathbone stated that he thought

Booth shouted "Freedom," as he jumped from the box. Although many of

the people present did not agree on Booth's words, it seems commonly accepted

that he spoke the Latin phrase.

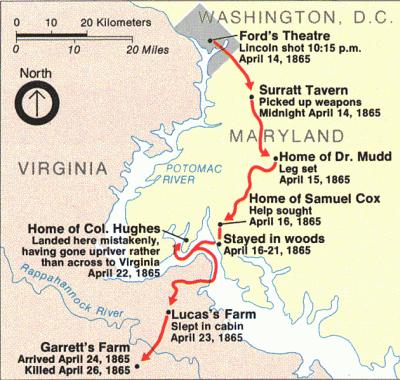

Sometime after 11:00 p.m., David Herold and

Booth, who both crossed the Navy Yard Bridge on their escape, met each other

around Soper's Hill. From here they traveled together en route to Lloyd's

Tavern, that was leased and operated by Mary Surratt in Surrattsville,

Maryland. The town's name was changed to Robeystown on May 3, 1865, and then

changed to Clinton on October 10, 1878, and remains so today.

At midnight, Booth and Herold

arrived at the tavern, after roughly an eleven mile journey from Ford's

Theatre. Once there, they drank whiskey and picked up the field glasses and a

Spencer rifle. In severe pain from the break in his leg, Booth needed medical

attention. Riding into the night, they came upon the house of Dr. Samuel Mudd

about four in the morning. Here, Dr. Mudd set Booth's leg. At this time, Booth

believed that his entire plan was a success. But, unknown to Booth, Paine

failed to kill Seward, although he did wound him, and Atzerodt refused to go

forward with his part of their plan, and never attacked Vice-President

Johnson.

On April 15, 1865 at 7:22

a.m., President Abraham Lincoln was pronounced dead, the result of a gunshot

wound inflicted by assassin John Wilkes Booth.

Just after Abraham Lincoln

had been shot on the evening of April 14, he was carried from his State Box at

Ford's Theatre across the street to the Petersen House, located at 453 Tenth

Street (now 516 Tenth Street). This house was owned by William Petersen, a

tailor, who rented out rooms. The room to which President Lincoln was taken

was rented by William T. Clark, who happened to be out of town. Being quite

tall, Lincoln did not fit on the bed, so he was placed on it diagonally. Extra

pillows were supplied so that Lincoln's head could be elevated. While Lincoln

was still alive, doctors, using a steel probe, located the .44 caliber lead

ball, but as it was lodged in his brain, removal was impossible. One

astonishing fact is that a few months before, this same room had been rented

by an actor named Charles Warwick. On one occasion, John Wilkes Booth visited

Warwick and fell asleep on the same bed on which Lincoln would later die .

The Search for Booth

After Dr. Samuel Mudd set

Booth's leg, he and David Herold stayed at the Mudd house until the following

night. On April 16, in their flight from Federal authorities, who were closing

in, they arrived at the home of Samuel Cox. Here, Cox gave them food and hid

them in the woods. On April 17, while President Lincoln's body was lying in

state at the East Room of the White House, Booth and Herold arrived in Port

Tobacco, Maryland, on the banks of the Potomac River. Here they searched for a

way to cross the river. Finally, after hiding out in Port Tobacco for a few

days, they crossed the Potomac River in a small fishing boat on April 20.

Meanwhile, Federal troops were searching for them, as well as anyone connected

with the assassination.

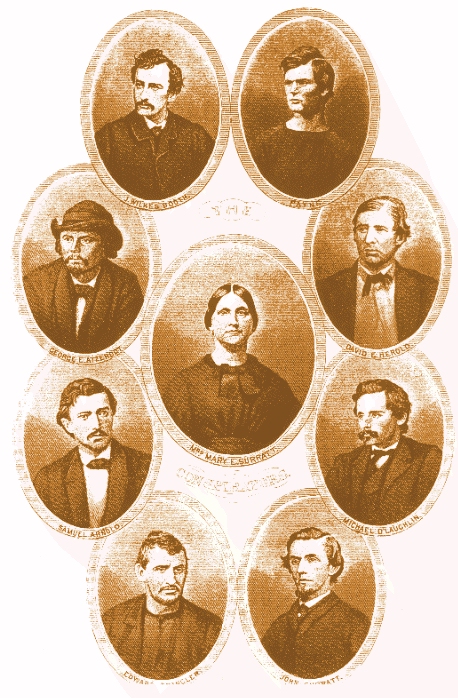

The Booth Conspirators

On April 24, Booth and Herold arrived at Port

Conway, Virginia. The next day, Federal troops traced Booth and Herold to a

farm owned by Richard H. Garrett, south of the Rappahannock River. Another man

named William Jett was a friend of Richard Garrett. It was Jett who provided

refuge for Booth and Herold at Garrett's farm. As he was never brought to

trial for aiding the two fugitives, Jett later settled in Baltimore as a

tobacco salesman. He died in an asylum, punishing himself for

the trouble he brought to Richard Garrett for hiding Booth and Herold.

On April 26, Federal troops surrounded the

tobacco shed in which Booth and Herold were hiding on the Garrett farm. Herold

surrendered, but Booth refused. Time and again, Federal soldiers ordered Booth

to surrender and each time, he failed to give up. To force

him out, the Federal soldiers set fire to the shed, and just as they did so, a

shot was heard, and Booth fell mortally wounded.

The origin of the shot, whether by a soldier

or self-inflicted is actually unknown, although it is credited to Sergeant

Boston Corbett, one of the Federal soldiers. Booth had been shot in the neck.

As he lay wounded, Federal soldiers carried him from the shed and placed him

on the porch of the Garrett home. One of the soldiers was sent to Port Royal

for a doctor, who did not arrive until daylight. When Booth was carried from

the tobacco shed to the porch he was unconscious, but soon came to. The doctor

had arrived while Booth was still alive, and tried to give him some medicine.

Booth, shaking his head said that it was useless and further stated, "Tell

my mother that what I did I did for the good of the country." Meanwhile,

the shed had burned to the ground, and soldiers were hunting in the ruins for

vestiges. They found two revolvers, that were ruined in the fire, however one

Federal soldier found Booth's carbine rifle. Booth died about three hours

after being placed on the porch. His body was wrapped in a blanket, laced in a

wagon and driven to Acquia Creek, Virginia.

Once at Acquia Creek, Booth's body was placed

on a boat, as well was Herold, who was closely guarded. Booth's body was taken

to Washington, D.C. where an autopsy was performed. Booth was then buried in

an unmarked grave at Arsenal Penitentiary. Today, the grave of John Wilkes

Booth is located in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland.

Note: In recent years, there has been

speculation that Booth's body is not that lays in his grave, whereby others

believe he had escaped capture and lived to an old age. This has not been

proven, and authorities indicate that he did die as related herein.

John Wilkes Booth's brother, Edwin, anguished

over the senseless act committed by his brother, expressed his sorrow in an

open letter to the citizens of the United States. It read:

New York, April 20, 1865

To the people of the United States.

My fellow citizens:

When a nation is

overwhelmed with sorrow by a great public calamity, the mention of private

grief would under ordinary circumstances be an intrusion, but under those by

which I am surrounded, I feel sure that a word from me will not be so regarded

by you.

It has pleased God to lay

at the door of my afflicted family the life-blood of our great, good and

martyred President. Prostrated to the very earth by this dreadful event, I am

yet but too sensible that other mourners fill the land. To them, to you, one

and all go forth our deep, unutterable sympathy; our abhorrence and

detestation of this most foul and atrocious of crimes.

For my mother and sister,

for my two remaining brothers and my own poor self, there is nothing to be

said except that we are thus placed without any agency of our own. For our

loyalty as dutiful, though humble, citizens, as well as for our consistent,

and as we had some reason to believe, successful, efforts to elevate our name,

personally and professionally, we appeal to the record of the past. For our

present position we are not responsible. For the future --alas! I shall

struggle on, in my retirement, with a heavy heart, an oppressed memory and a

wounded name --dreadful burdens -- to my welcome grave.

Your afflicted friend,

Edwin Booth

In 1863, Edwin Booth's wife,

Mary Devlin died. In 1865, he was still mourning her death when this dreadful

act by his brother struck him another hard blow. In his letter above, he vowed

to never perform again. However, when extreme debt drove him back to the

stage, less than a year later, his public celebrated. Not blamed for the act

of his brother, Edwin regained his name and trust of the citizens of the

United States, and was welcomed as a performer on the stage. Not far from

their home at Tudor Hall, is the Edwin Booth Theater, so named in his honor.

It is located on the campus of Harford Community College, in Bel Air,

Maryland.

The Surratt House and Museum,

Clinton, Maryland

http://www.surratt.org/

This is a photograph of an actual

US Flag that was hand made by my great grandmother, Mrs. John Daniel

Webster Thayer, originally intended to be flown at the end of the

Civil War in 1865. The black mourning stripe was added and

flown for the funerals of Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield,

Ulysses S. Grant, Warren Harding, and William McKinley. In

1941, she gave this flag to my father, William John Marck, Jr., who

passed it down to me in 2008. Sadly my father passed away on July

25, 2008. This flag has been in my family since 1865. As it was

first flown for the funeral of Abraham Lincoln, I thought it

appropriate to include it here.

Copyright © 1993-2022 by John T. Marck. Information for

this article came from a variety of excellent sources. These include: Tudor

Hall, Bel Air, Maryland, the home of John Wilkes Booth, and to Howard and

Dorothy Fox, who spent many hours with me telling me stories of Booth and his

last days, as well as his family, living at Tudor Hall; The Surratt House

Museum, Clinton, Maryland; My father, William John Marck, Jr., a historian and

teacher; Springfield, Illinois and the National Park Service at the Lincoln

Home National Historic Site; Blood On The Moon, by Edward Steers, Jr.,

The University Press of Kentucky, 2001; A True History of the Assassination

of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865 by Louis L. Weichmann,

Alfred A. Knoff Publisher, New York 1979; Lincoln by David Herbert

Donald, Simon and Schuster, 1995; The Death of Lincoln by Clara

E. Laughlin; and the section, "The Objects of Lincoln and Booth," from

Time-Life; The Escape and Capture of John Wilkes Booth by Edward Steers; and

information received from a speech by Kate Clifford Larson about Mary Surratt

regarding her book, "The Assassin's Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the

Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln" et al. Please also see:

www.aboutfamouspeople.com/article1147.html

|