| |

Home

Famous and Fascinating Women in History

Frontiersmen and Women

The World's Greatest Composers

Famous Women Spies

Great Authors of the World

Generals and other Noteworthy People

from the Civil War

The Presidents of the United States

The First Ladies of the United States

Homes and Monuments of and to

Famous People

Historical People and Events by Month for Each Day of the Year!

Famous Figures in Black History

The Calvert Family and the Lords Baltimore

Understanding the American Revolution and its People

Everything Beatles!

Everything Maryland! |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|  | |

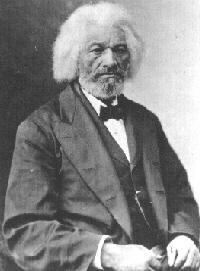

The life of the famous abolitionist and journalist, who

emerged as a major anti-slavery force,

and a supporter of women's rights.

Frederick Douglass

By John T. Marck

Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in February

1818. He was born on a farm on Lewiston Road, Tuckahoe, near Easton, in Talbot

County, Maryland. Frederick was the son of an unknown white father, and Harriet

Bailey, a slave who was a part African and Native American. Frederick was born a

slave on the great plantation owned by the Lloyd family. At times, they referred

to him as Frederick Lloyd. When he was eight years old, he was separated from

his mother and never saw her again. Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in February

1818. He was born on a farm on Lewiston Road, Tuckahoe, near Easton, in Talbot

County, Maryland. Frederick was the son of an unknown white father, and Harriet

Bailey, a slave who was a part African and Native American. Frederick was born a

slave on the great plantation owned by the Lloyd family. At times, they referred

to him as Frederick Lloyd. When he was eight years old, he was separated from

his mother and never saw her again.

As a child, Frederick was legally classified as real estate

or property rather than as a human being. He experienced much neglect and cruel

treatment, and hard work brought on by the tyranny toward slaves. Resistance by

slaves usually resulted in even more cruel treatment. However, in Frederick’s

case it paid off. By fighting back toward his cruel master, Colonel Lloyd, and

following a failed escape attempt, he was sent to Baltimore as a house servant

at the age of eight. In Baltimore he learned to read and write with the

assistance of his mistress, although was mostly self-taught. Having now learned

to read and write he soon began to conceive of his freedom. Frederick was

fortunate in that the Lloyd family often would severely whip slaves who were

hard to manage or who tried to escape, then sent them to Baltimore, only to be

sold to a slave trader, as a warning to all other slaves.

Upon the death of his master, Frederick was returned to the

country as a field hand. Here, he conspired with six other fellow slaves to

escape. Their plan a failure, and betrayed by another, he was placed in jail.

His new master, being a tolerant sort, arranged for his release from jail and

returned him to Baltimore. Again, in Baltimore, Frederick learned the trade of a

ship carpenter, and in time, was permitted to hire his own men.

On September 3, 1838, Frederick made another escape attempt,

and this time was successful. He traveled to New York, changed his last name to

Douglass, and married a free black woman named Anne Murray, whom he had met in

Baltimore earlier. Together they moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where

Frederick worked as a laborer.

In search of a new career, Frederick read Garrison’s

Liberator, and in 1841 attended a convention of the Massachusetts

Anti-Slavery Society in Nantucket. One of the attending abolitionists overheard

Douglass speaking with some of his black friends. Impressed, this man asked

Douglass to speak at the convention. Although reluctant, he did so, and although

he stammered, his speech had a remarkable effect. As a result, and to his

surprise, they immediately employed him as an agent to the Massachusetts

Anti-Slavery Society, and a new career was born.

In his new position, he participated in the Rhode Island

campaign against the new constitution that proposed the disfranchisement of

blacks, which denied them the right of citizenship and the vote. He was the main

figure in the famous "One-Hundred Conventions," of the New England Anti-Slavery

Society. Here he was mobbed and beaten and forced to ride in "Jim Crow" cars and

denied overnight accommodations. ("Jim Crow" refers to the "legal" repression of

slavery or segregation). Yet through this all, he remained and saw the planned

program to the end.

Douglass possessed a strong physique, being more than six

feet tall, with a strong constitution and an excellent speaking voice. Because

of this, those who heard him speak, began to doubt his story of having ever been

a slave, and that he was basically self-taught. Because of these doubts,

Frederick wrote his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. However,

a friend, Wendell Phillips, advised Douglass to burn the book because he

recounted his life as a slave, and Phillips believed releasing it would re

enslave Douglass. Douglass refused and published the book in 1845. However, to

avoid any possible consequences, he traveled to Great Britain and Ireland. He

remained there for about two years where he had the opportunity to meet and get

to know the English Liberals. In this environment, they treated him as a man and

an equal for the first time in this life. This resulted in improving his

character and self-esteem. From this experience, he truly started to believe

that freedom, not only physical, but social equality and economic and spiritual

opportunities were possible.

In 1847, he returned to the United States, and having enough

money, he bought his freedom and established a newspaper dedicated to his race.

Many of his white abolitionist friends disagreed with his views in this

newspaper, and others believed that the ability to purchase his freedom was in

fact condoning slavery. However, Douglass, upon learning these criticisms,

handled them in a practical manner.

Douglass went on to establish his newspaper, the North

Star, and published it for seventeen years. Furthermore, he lectured, was a

supporter of woman suffrage, took an active part in politics, and helped Harriet

Beecher Stowe establish an industrial school for black youth. He also met with

John Brown, and counseled him. Upon Brown’s arrest, the Governor of Virginia

attempted to arrest Douglass as a conspirator. To avoid arrest, Douglass fled to

Canada, then England and Scotland, where he again lectured.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, additional opportunities

came his way, by which he passionately fought against slavery as its major

cause. He assisted in convincing black men to join the Union army, and he helped

in recruiting for the 54th Massachusetts colored regiment, offering his own sons

as the first recruits. Twice during the war, President Lincoln invited him to

the White House to discuss important matters concerning the black soldiers in

the Union Army.

Following the Civil War in 1877, Douglass was appointed as

United States Marshall for the District of Columbia by President Hayes, and in

1881, President Garfield appointed him Recorder of Deeds for the District of

Columbia.

In 1884, Douglass married again. His second wife was Helen

Pitts, a white woman, which brought about much criticism. Concerning this, he

maintained his sense of humor by saying, "my first wife was the color of my

mother, and my second wife, the color of my father." In 1891, President Harrison

appointed Douglass as Minister-Resident and Consul-General to the Republic of

Haiti, and as Charge d’affaires for Santo Domingo.

On June 22, 1894, Douglass gave an address at the Sixth

Annual Commencement of a Colored High School in Baltimore, Maryland. In his

address, Douglass said: "The colored people of this country have, I think,

made a great mistake, of late, in saying so much of race and color as a basis of

their claims to justice, and as the chief motive of their efforts and action. I

have always attached more importance to manhood than to mere identity with any

variety of the human family..." "We should never forget that the ablest and most

eloquent voices ever raised in behalf of the black man’s cause were the voices

of white men. Not for race, not for color, but for men and for manhood they

labored, fought, and died. Away, then, with the nonsense that a man must be

black to be true to the rights of black men."

Frederick Douglass died on February 20, 1895. Active to the

end, on the day he died, he attended a woman-suffrage convention.

Copyright © 1993-2022 by John T. Marck. All Rights Reserved. This article

and their accompanying pictures, photographs, and line art, may not be resold,

reprinted, or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written

permission from the author.

| | |

| |

|